A rich cultural space – feeding people and community for millennia

From sandbar to heavy industry, produce market to community spaces, Granville Island CMHC continues to evolve. A statement reviewed by Chief Janice George Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) provides a brief context of the Coast Salish connections to this place.

VHF’s NE Kitsilano Map Guide touches on the area:

“For more than 10,000 years, people have lived in the place only recently known as Vancouver. For generations, the sandbar that became Granville Island was an important fishing spot for Coast Salish people. Using a tidal weir of vine maple fencing and stinging nettle fibre netting, they corralled fish, like flounder and smelt, in the narrow channel formed between the island and the south shore of False Creek.”

The history of this place is told by the Musqueam First Nation:

“Burrard Inlet was also part of our core hunting and fishing area. Our families stayed at sən̓aʔqʷ while hunting elk and waterfowl. was also important for harvesting and processing salmon, sturgeon, and smelt that frequented False Creek and its many streams, many of which have been lost to urbanization and development.”

When you enter the Island today, you may spot the pillars of the Granville Street Bridge, wrapped in Coast Salish textile patterns. In 2018, artist and weaver Qwasen (Debra Sparrow), VMF and Granville Island partnered to produce Blanketing the City. Debra’s studio Salish Blanket Co. is also located on the Island, connecting design, heritage, culture and revitalizing the Coast Salish weaving traditions of this place.

How has this place transformed into the place we know it today?

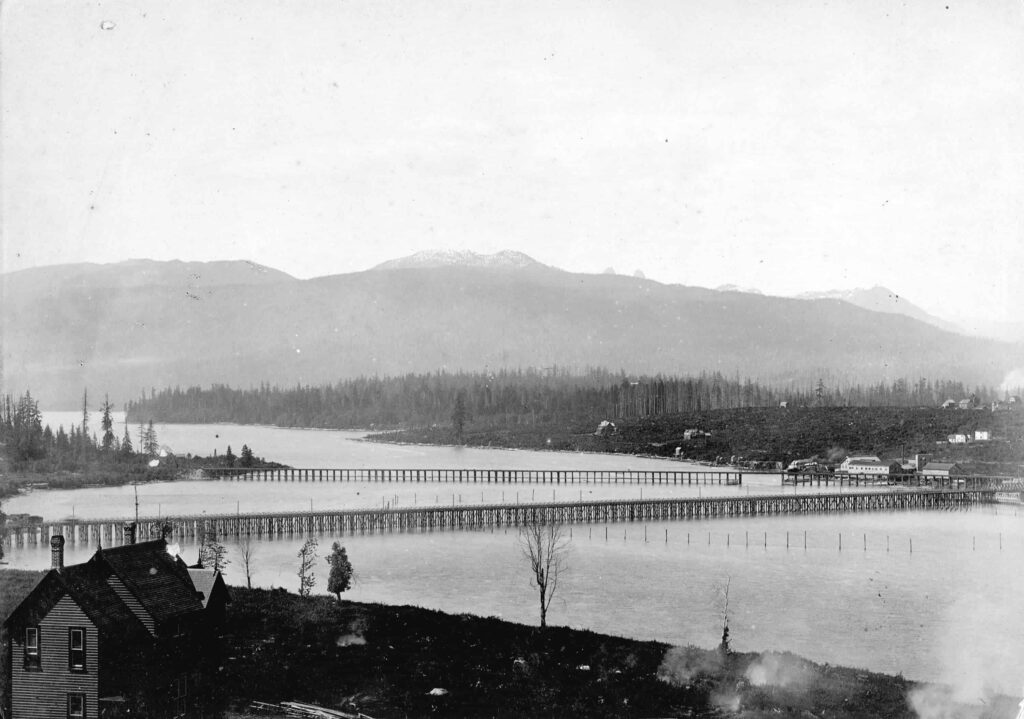

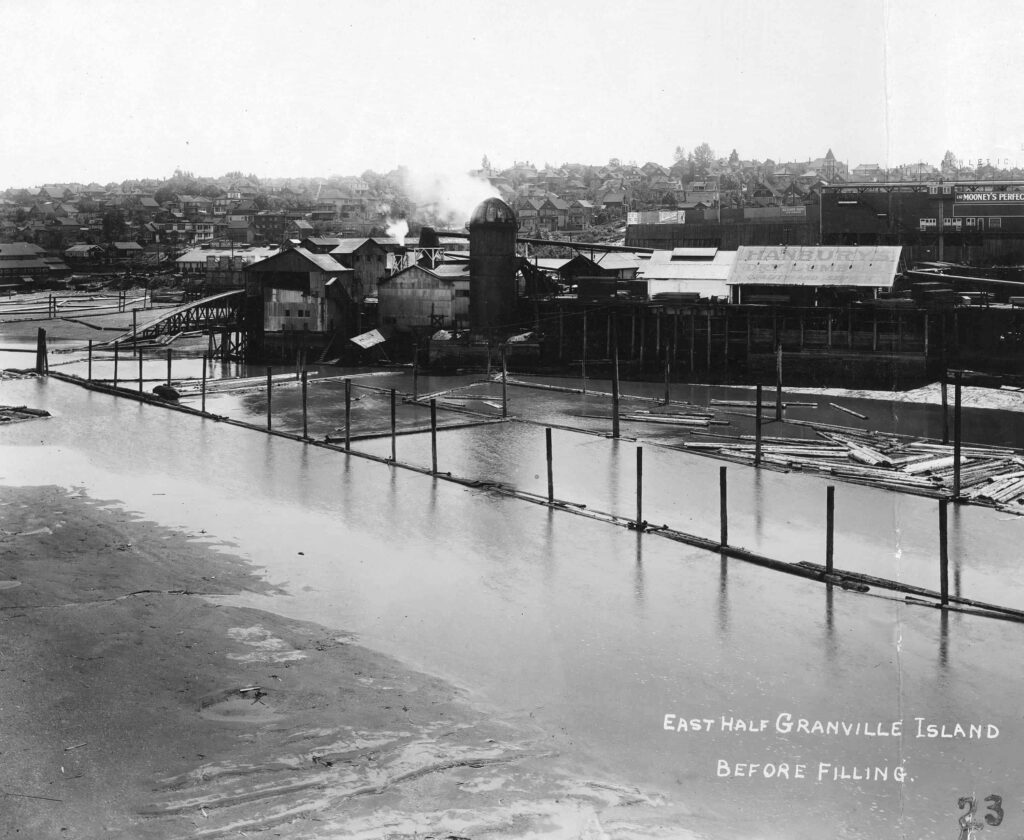

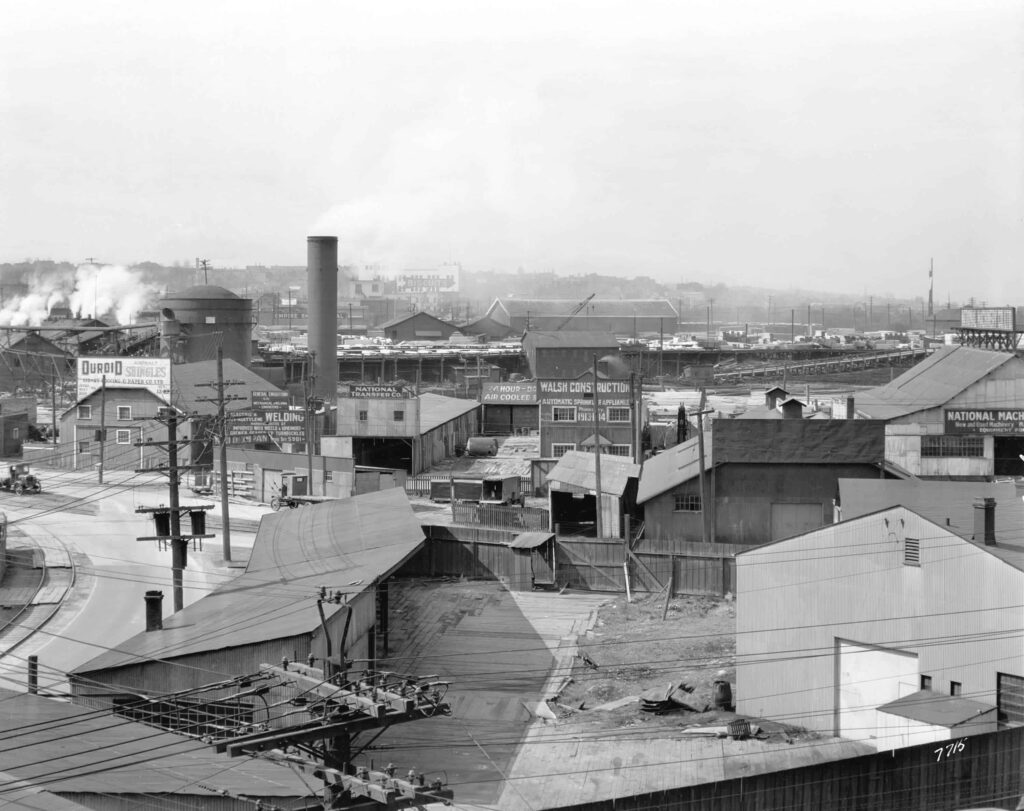

Industrial Island – 19th century

False Creek in the 1870s: Settlers established sawmills and logging roads on either side of the False Creek, and when the first Granville Bridge connected the shores of False Creek in 1889, the south side became even more desirable. The CPR, government and local businessmen fought over the sandbars and water rights until 1916, when it was transferred to the National Harbour Commission (NHC). The NHC quickly built a seawall around the sandbars, filled it with mud sucked from the bed of False Creek, and built a wooden road and railway to the island. About 40 acres of leasable land was created and businesses, mostly factories and mills, were quick to move in, building post and beam structures clad in corrugated tin. It was called Industrial Island, and at its height in the 1930s, there were 1200 people employed by 40 industrial companies, which manufactured and supplied fibre, rope, chain, and materials for logging, mining and shipping. The Depression years saw a decline in industry, but WWII reinvigorated the island, and industries switched to manufacturing defense equipment, employing women for the first time. It was during the war years that the name Granville Island started to be used.

Decline of Industry- mid-1950s

With the end WWII came the slow decline of industry on the island. Trucking was becoming the more common method of transportation for industries, and water access was less in demand. There were a series of fires in the 1950s, and the island had become so run-down that it was easier for companies to move away than to fix up their buildings, and industries were moving to the suburbs en masse. It was also in these years that Granville Island stopped being an island; plans to fill in False Creek got as far as filling in what is now the Sutcliffe park area, connecting Granville Island to the mainland permanently.

Revitalization 1970s

The Canadian Housing and Mortgage Corporation (CMHC) was working on the redevelopment of south False Creek, and in 1973, took ownership of Granville Island. The renewal of Granville Island began with the expectation that the island would become a “people place,” existing buildings would be reused as much as possible, and the industrial maritime heritage would be retained.

The overall plan for Granville Island’s revitalization was designed by Joost Bakker and Norman Hotson of DIALOG. Because the island was not under the jurisdiction of the City of Vancouver, unique aspects like the unseparated foot and road traffic were possible. Hotson remembers that “when we did Granville Island we took a lot of chance,” and “it was a place where different types of public uses, private uses were converging a dynamic city on the waterfront.” The design of Granville Island won several awards, and has been an inspiration for revitalization and urban development in other cities.

Starting in 1975, formerly industrial buildings were rejigged for a wide variety of tenants such as studios, shops, markets, restaurants, community groups etc. The corrugated tin was painted bright colours, while outdoor spaces were revamped. It was all planned so that Granville Island would be destination year round, and would be used day and night. The centrepiece of Granville Island is the Public Market, one of the first buildings to reopen, in 1978. It is made up of six old industrial buildings, including BC Equipment Ltd, the first tenant on the island in 1917, and Wright’s Ropes, which was nearly destroyed by a fire in the 1950s.

Granville Island: 1980s-Present

What memories do you have of the Island?

The Future: Granville Island 2040+

In 2017, CMHC presented Granville Island 2040, a revitalization plan which includes a proposed elevator and stairway connecting the middle of the Granville Street Bridge to Granville Island below. Current maintenance work continues to take place and new initiatives have included a covered skate ramp with VSC, major companies like Arts Umbrella and Ballet BC as tenants, as well as longstanding Heidelberg Cement (formerly Ocean), which hosts an open house every spring.

Nearby Places That Matter

Sources

- Fazel, Yasaman. “The Hidden Heritage of Gem of B.C.: The Economic and Architectural History of the Granville Island Public Market.” UBC Undergraduate Research. 30 April, 2016.

- Gourley, Catherine. “Granville Island.” In The Greater Vancouver Book edited by Chuck Davis. Surrey, BC: Linkman Press, 1997.

- “Granville Island.” History of Metropolitan Vancouver website.

- “Granville Island Redevelopment.” Dialog Design website.

- Granville Island 2040 website

- Granville Island website

- Kalman, H. and Ward, R. Exploring Vancouver. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2012.

- Meuse, Matt. “How Granville Island changed the course of Vancouver urban design history.” CBC News, 12 March 2017.

There is no physical plaque onsite- please contact us if you are interested in sponsoring this plaque!

There is no physical plaque onsite- please contact us if you are interested in sponsoring this plaque!