Strathcona Neighbourhood

With its proximity to both False Creek and the Burrard Inlet the area that became Strathcona, is traditional Coast Salish land. By the 1860s, the area was home to the sawmill industry, and once the CPR designated the Burrard Inlet at their terminus station in 1877, there was a rush to buy properties. David Oppenheimer’s company Vancouver Improvement Company owned much of the land in Strathcona and began selling lots in 1886, priced from $100-1000. The residential area developed quickly, with simple wooden houses, and was home to the working class and a tight knit community, Vancouver’s first “neighbourhood.”

A Lutheran Church

In 1881, both lots that now make up 823 Jackson Ave were owned by Swan G. Hoffard, a Norwegian grocer, but in 1894, the lots were split, with the north side bought by Carl J. Olson, the pastor of a Scandinavian Lutheran congregation, while the north side was retained by the Hoffards. The first building at 823 Jackson Ave, built around the same time, was a small one-storey church called First Scandinavian Lutheran Church. A German Lutheran congregation is also listed as having used the site from 1900-1905, after which they moved to their own church, and the Scandinavian Lutheran congregation split into separate Norwegian and Swedish congregations, leaving the Norwegians at 823 Jackson. It was 1910 that the Norwegian congregation commissioned a new building, which later became Fountain Chapel. Historian James Johnstone has compiled a history of the Lutheran church.

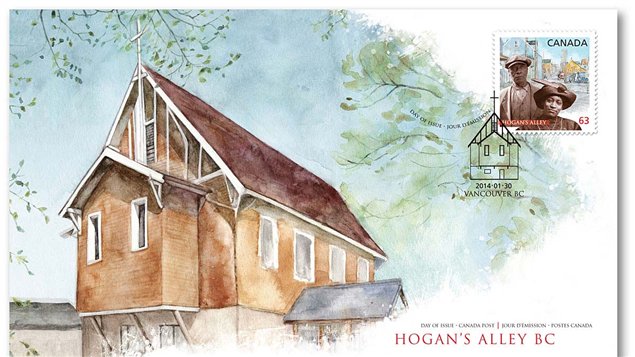

Designed by Frederick Mellish, the new arts and crafts style church was later used by the the African Methodist Episcopal Church congregation, and still remains on the site today. Mellish, an architect from Ontario, was known for residential, commercial institutional projects in his home province, and had a limited career in Vancouver, designing only this church, St. Saviour’s Anglican Church at E 1st and Semlin (now the Vancouver Mandarin Church), and a few residences, including his own at 2325 E 1st. Fountain Chapel, a 1 ½ storey gabled church, is a rare example of an Arts and Crafts institutional building, with a simple aesthetic, steeply pitched gable roof, shingle siding and trim and half timbering. It is one of Canada’s Historic Places, and a registered heritage building. The church was built around the same time as houses in the neighbourhood, and many heritage residences remain on the surrounding streets.

The Beginnings of a Black Community

In 1858, approximately 800 Black people moved to Vancouver Island from California, on the invitation of Governor James Douglas. Over the next couple decades, Vancouver became the economic centre of the province, and people were moving en masse to the city. By 1871, there were over 500 people of African Descent living in Vancouver, with a number in the Strathcona area, an area also home to many Italian, Japanese and Chinese immigrants. A later wave of migration saw Black immigrants coming from Oklahoma, by way of Alberta, and settling in Strathcona and other parts of the city.

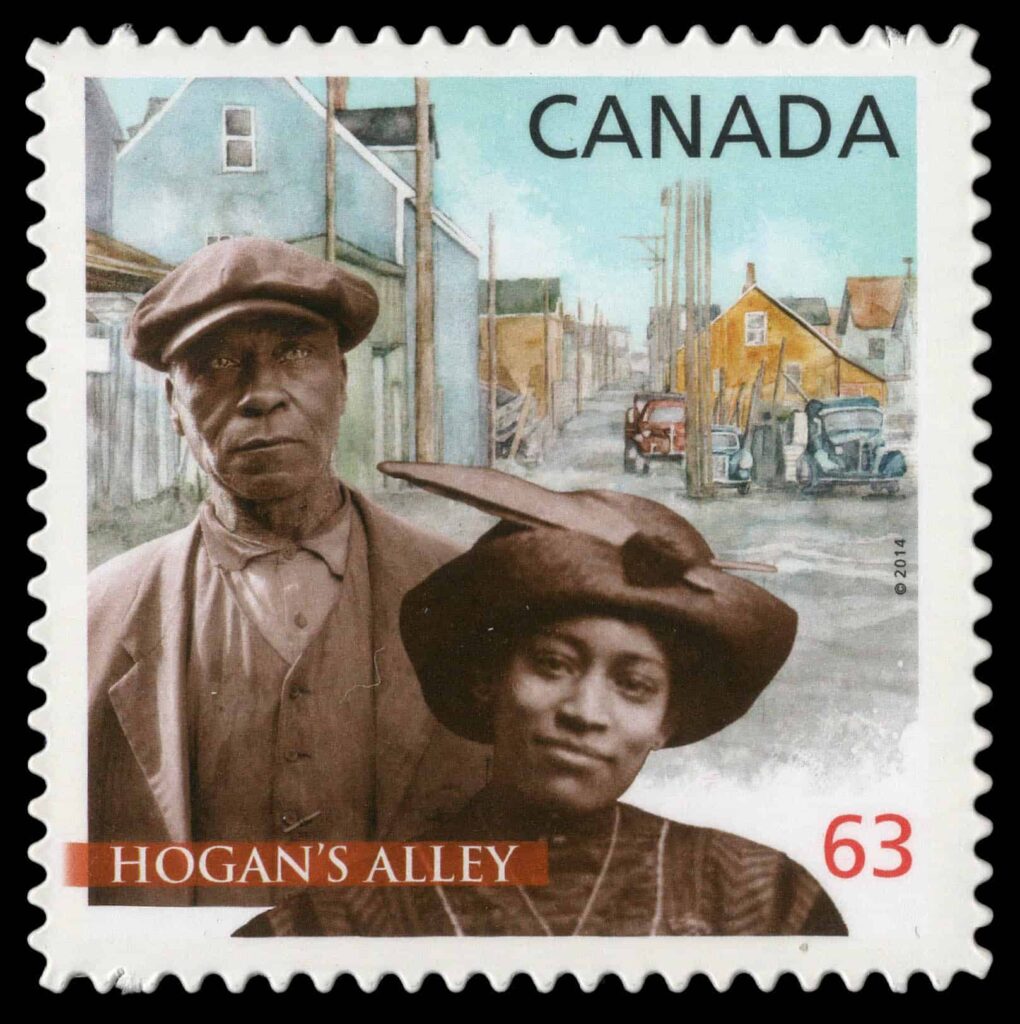

By 1910, Hogan’s Alley, which ran between Union and Prior Streets, from Jackson Avenue to Main Street, was a well known and lively commercial centre of the community. The Black Strathcona website is also a great place to check out more stories of the neighbourhood and its residents, or the Vancouver Heritage Foundation page on Hogan’s Alley.

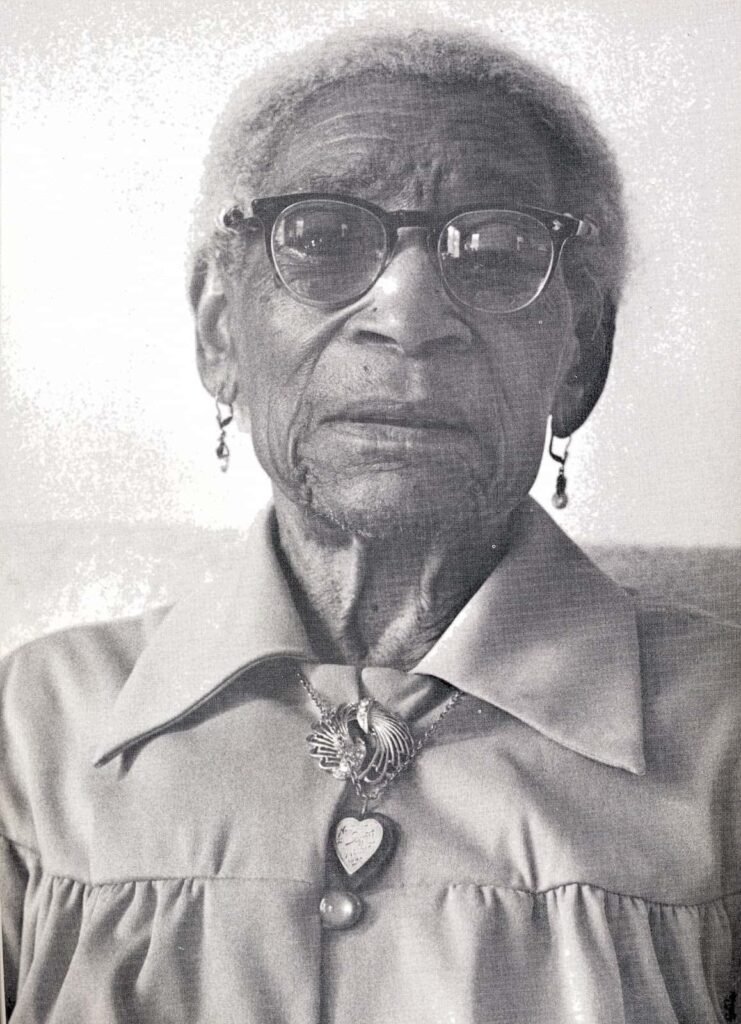

In 1911, Nora Hendrix and her husband James settled in Vancouver. Nora is known as a driving force behind the foundation of the African Episcopal Church congregation in Vancouver (as well as for being the grandmother of Jimi Hendrix). Nora and James’ home from 1938-1952 is just two blocks away from Fountain Chapel (827 E Georgia), designated a Heritage Site and is one of Canada’s Historic Places.

Raising Money for a Church

With Nora Hendrix as a leader, the Black community in Strathcona looked for a church, after spending years worshipping out of rented halls. As Nora put it, “nobody had ventured out to try and get a church for their own.” The community contacted the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.), who offered $500 towards a church, if the community was also able to raise $500.

“All the families and everybody that wanted a church, we all got together, and commence working for it to get this church started,” said Nora in her interview for Open Doors. It wasn’t easy work. At that time, an average daily wage was only $1.50, and it took time and effort to raise the money. The community held fundraising bazaars, suppers and entertainment, and in 1918, they were able to buy the old Lutheran Church.

Fountain Chapel: 1918-1950s

At the eastern end of Hogan’s Alley, the church became the cultural hub of the community, and was always busy with services, dinners, bazaars, meetings and events. It also started a choir, which Nora was part of, which would sing at the church as well as venues around the city. Nora fondly remembers large gatherings at the church for American Thanksgiving, and regular chitlin dinners that would quickly sell out (Opening Doors).

Fountain Chapel’s first reverend, in 1921, was Ulysses S. Robinson from the United States, who stayed for nine years. After that there was a string of reverends over the years. Reverend J Ivan Moore, the first Canadian born reverend at the church, took his post in 1952, and was known for his work with youth, including a Wednesday night youth group. For more information on the Fountain Chapel’s reverends see the EastVangelist blog, and the post on When An Old House Whispers.

True to the founding principles of the A.M.E., the Vancouver congregation was active in the community, fighting racism and injustice. In 1923 the congregation guaranteed a fair trial for Fred Deal, a railroad porter accused of murder, and in 1952, and inquiry into the police brutality and killing of longshoreman Clarence Clemons.

A Changing Neighbourhood: 1930s-1980s

The heydays of Hogan’s Alley were the 1920s and 30s, but in the 1930s, the City changed the neighbourhood’s zoning, making it harder to secure mortgages and money for renovations, in efforts to stop further residential development in an area they had labelled a “slum.” In the 1950s and 60s, the City stopped maintaining the area’s roads and sidewalks, and the community began to disperse. Those who stayed in the neighbourhood worked to fight plans for urban renewal, particularly in 1967, when a plan for a freeway through Strathcona and Chinatown was announced. Although the plan for a freeway was abandoned, in 1972, two blocks of Hogan’s Alley had already been destroyed to make room for the new Georgia Street Viaduct.

In the 1960s, as the neighbourhood went through great change, numbers at Fountain Chapel were dwindling. During that time, a woman named Annie Walker had started her own non-denominational congregation, and was sharing the building with the A.M.E. In 1969, Annie, now remarried and going by Annie Girard, bought the building, naming it Cry in the Wilderness Church and in 1977, Girard bought the south section of the lot, reuniting the two halves once more.

Chinese Church and Residence

In 1985, the church was bought by the Basel Hakka Lutheran congregation, who offered services in Chinese and English. From 2002-2008 they raised money for a larger space, and bought a building at 2575 Nanaimo St. In 2008, the church was decommissioned and bought by a couple as their private residence. November 1, 2008, a special ceremony was held for the last service of the church, and members of the Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project attended. Strathcona has gone through many changes over the last century, but it will be remembered as part of the lively and thriving cultural and spiritual centre of Vancouver’s Black community for over 60 years.

Today, the private residence has been called Churchland Studios. The site does not currently have a PTM plaque installed.

On February 24, 2019, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (Fountain Chapel), in collaboration with African Descent Society British Columbia, held a 100th anniversary celebration (1918-2018) at 897 Keefer St along with a walking tour, to reconnect the congregation and revive the history of the area.

Nearby Places That Matter

Sources