I found a 1921 census that showed 14 households living in the apartment building.

One of the residents then was Seiya Tonogai's son, Nobuo.

He was born and raised in the house until he was 6.

He went back to Japan with his mother and younger brother to attend school in Japan.

His father, Seiya stayed in Canada to work at a saw mill,

He was to join his family in Japan later.

Nobuo's younger brother died in 1923 at age 2, and his father died in a saw mill accident in 1924.

Nobuo's mother worked at a sewing factory and raised Nobuo.

When Nobuo turned 21, in 1938, he was drafted and sent to China to engage in the Sino-Japan war.

He survived and return to Japan.

He was to live with his own family, but he was drafted again a few days before the Pearl Harbor attack, in 1941

He was sent to the Philippines to engage in the Pacific war.

His son was born while he was in the Philippines, three months after he was drafted.

He caught malaria and was hospitalized for 12 days and sent back to the battle.

He survived three operations in the Philippines and returned to Japan in 1943.

When he was transferred by the train to be released from the army,

he passed by his hometown of Hikone with other soldiers.

He wrote many notes in which he said he returned safe and sound,

and threw them out of the window as the train passed through Hikone.

One of his family's neighbors found a note and brought the news to his family.

That's how his family learned of his safe return.

Nobuo came to Canada in 1995, with his two grand sons at age 78.

I think he wanted to see Vancouver, his birth place, again in his life.

He was surprised and cried to see the 1017 House.

He had his picture taken in front of the 1017 house,

and kept it in his room until he passed away in 2013.

This is the picture.

He remembered riding a tricycle on the slope near the house.

This is a picture of him as a child in Vancouver.

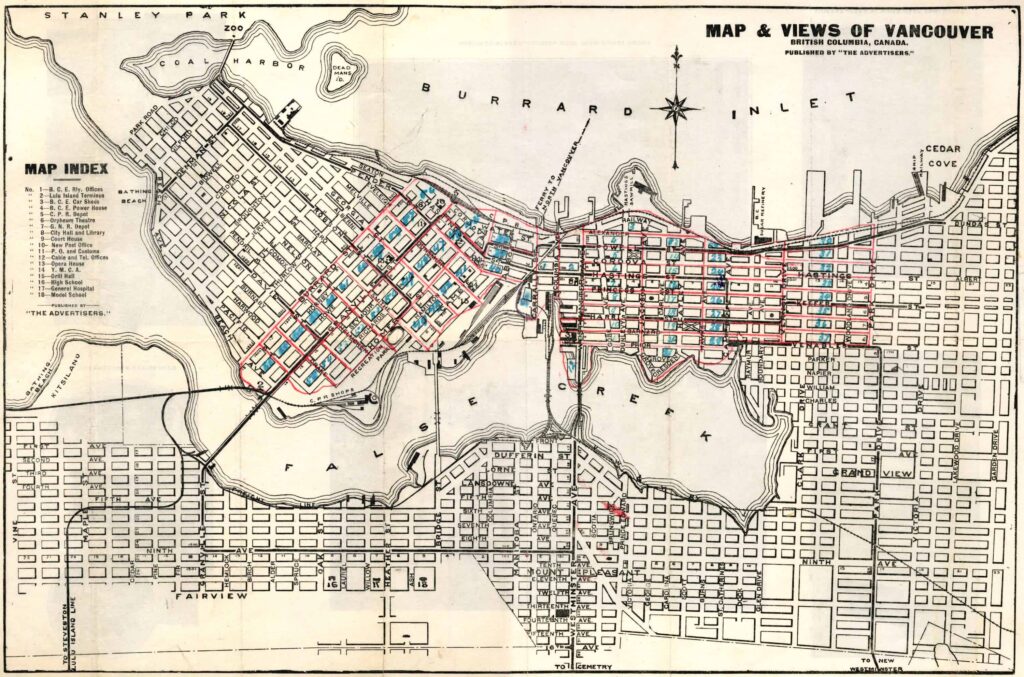

Early History of Fairview

Traditional Coast Salish land, indigenous people were the only residents of Fairview until the 1860s, and the area was covered in forest until logging began in the 1870s in order to feed Hastings Mill. Fairview in the last decades of the nineteenth century saw increased development. In 1889, the first Granville Bridge opened followed by the first Cambie Bridge in 1890. The Fairview Beltline streetcar service began in 1891, which traveled from downtown over the Granville Bridge and along what is now Broadway, spurring housing development in the area. Housing settlement, especially for those working in sawmills and other industry in the area, began on West 3rd and 7th Avenues (a logging trail leading to Kitsilano Beach). At the turn of the century, Fairview’s settlement was still scarce, with the development boom happening in 1912.

Japanese and Nikkei in Vancouver

Many workers in Vancouver’s early sawmills were immigrants from Japan and those of Japanese descent born in Canada (Nikkei,), as well as South Asian and Indigenous people. The first known Japanese immigrants in Vancouver were thought to have settled in the late 1870s. In the 1880s, the majority of Japanese in Vancouver were working in industries such as sawmills, canneries, or in fishing. Many lived near the Hastings Sawmill near Powell Street, or Paueru-gai, while others lived in Kitsilano or along the Fraser River (Celtic, Marpole/Eburne). In the 1890s, Japanese Canadians began to establish boarding houses for workers, as well as businesses in the Powell Street area. As industry and housing in Fairview boomed in the early 1900s, more mills and housing for workers were established in the area.

1017 W. 7th Avenue and “Fe-a-byu” (Fairview)

Genya Yada and his co-worker Rinnosuke Takehara built this tenement in 1913 to house Japanese workers who laboured at the various mills in False Creek during the industrial boom in the early 20th century. The building is perhaps the last and only tenement example of those days that survived urban renewal in many forms during the 60’s-90’s. In the early boomtown days, the city was full of low cost housing and innovative ways to house poor and transient labourers.

The tenement is long and narrow, only 18 feet wide and 110 feet long. It is built on a grade, which slopes from 7th to 6th Avenue, and is two stories at street front, drops down to three stories, then four stories at the lane. A narrow catwalk spans the length of the east side of the building and drops to the different levels. Unlike many tenement buildings in Vancouver, it was built with the intention to house workers with their families, and Yada called it the “cabin.” The building permit dates to 1912, issued to Genya Yada, designed by G. Matsuka, and states construction costs of $2500.

Intact today are apartments which were converted from the original rooms. The building is currently for sale and is on the Heritage Vancouver Top 10 Watch List. Read the CBC article on the eldest Yada grandson seeing the inside of the building for the first time on June 9, 2018.

Genya Yada and family

Genya Yada was from Chimoto mura, aza Higashi Nonami in Shiga Prefecture, considered a place that produced many entrepreneurs and many immigrants to Vancouver. Genya immigrated to Canada in 1897 and Shige Teramura came in 1906. They were married in 1907 and lived in the rooming house on West 7th, where their children were born. In the early days, there were about 500-600 workers living near the sawmills in False Creek, an many families lived in their rooming house.

The Yada’s oldest son, Genichiro took English language classes in Fairview and worked in the sawmill. He then worked for Crown Life Insurance and set up a shop called Cassiar General Store at 3390 Hastings in 1927. Genichiro also helped his father-in-law Teramura with his sawmill business near Main St and 5th Ave called Kurt Randle Company.

The Yadas moved out of the ‘Cabin’ on West 7th Avenue in about 1927 (after 14 years) to set up the Cassiar General store on the lower level at 3390 Hastings with family accommodation on the upper level, and a backyard for the children. They had land and plans to build an apartment building and another store, but those plans were halted with the Internment, or mass forced evacuation. The Yadas were sent to Bridge River, a self supporting camp near Lillooet (250km from Vancouver), and received a pittance for the sale of their properties. Their savings supported them for three and a half years, until the camp closed and they moved to Devine, near Lillooet, to work in the sawmill. When allowed to return to the coast (after 1949), the family did resettle in Vancouver.

- For more information on the Yada family history, read the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre Archives’ research: Takehara Yada Apartments

Related Places That Matter, Japanese Canadian History

Sources

- 2018 research by the National Nikkei Museum and Archives, Linda Kawamoto Reid c/o Yada family.

- Fe-a-byu booklet from NNMA website.

- Nikkei National Museum and Culture Centre Website.

- 2018 Top Ten Watch List. Heritage Vancouver Website.

- Nikkei Stories Website.

- Smedman, Lisa. Immigrants: Stories of Vancouver’s People. The Vancouver Courier Newspaper, 2009. Vancouver: Stories of a City. The Vancouver Courier Newspaper, 2008.

- Davis, Chuck. The Greater Vancouver Book: An Urban Encyclopaedia. Surrey, BC: The Linkman Press, 1997.