The City of Vancouver is located on the ancestral, unceded and traditional territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səlil̓wətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples.

Learn more on the Musqueam Place Names Map, First Peoples’ Cultural Council of BC’s First People’s Map of BC and the Squamish Atlas. Further resources can be found on VHF’s Indigenous Heritage Resources page.

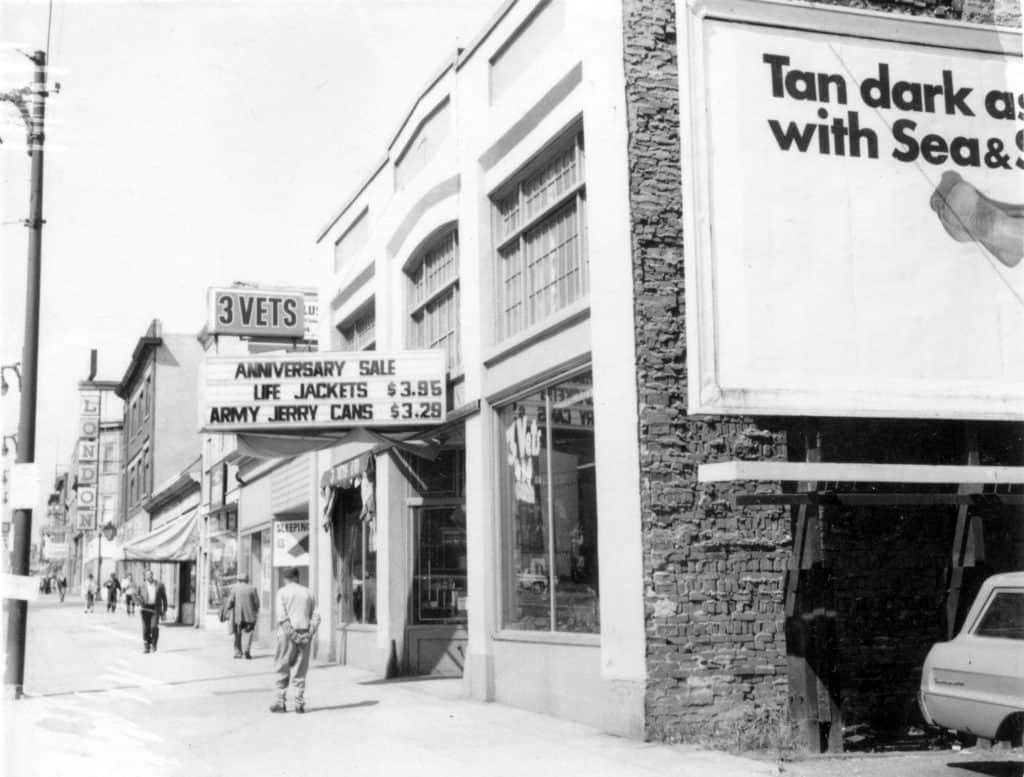

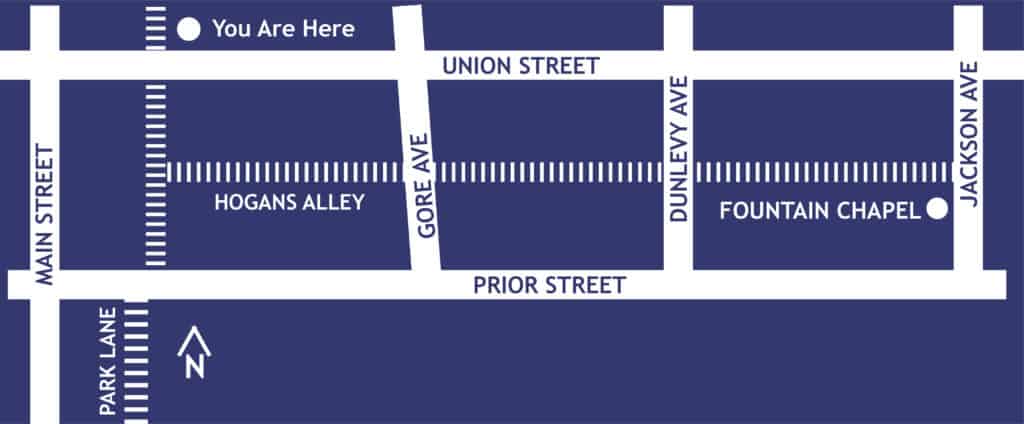

Hogan’s Alley was the unofficial name for a T-shaped intersection at the southwestern edge of Strathcona that formed the nucleus of Vancouver’s first concentrated Black community. Vancouver’s first archivist, J.S. Matthews (see Major Matthews’ House), noted that the name “Hogan’s Alley” was in use by 1914. As shown on the illustrated map above, Hogan’s Alley was located in the lane behind the 200-block of Prior and Union streets, between Gore and Main streets.

The East End

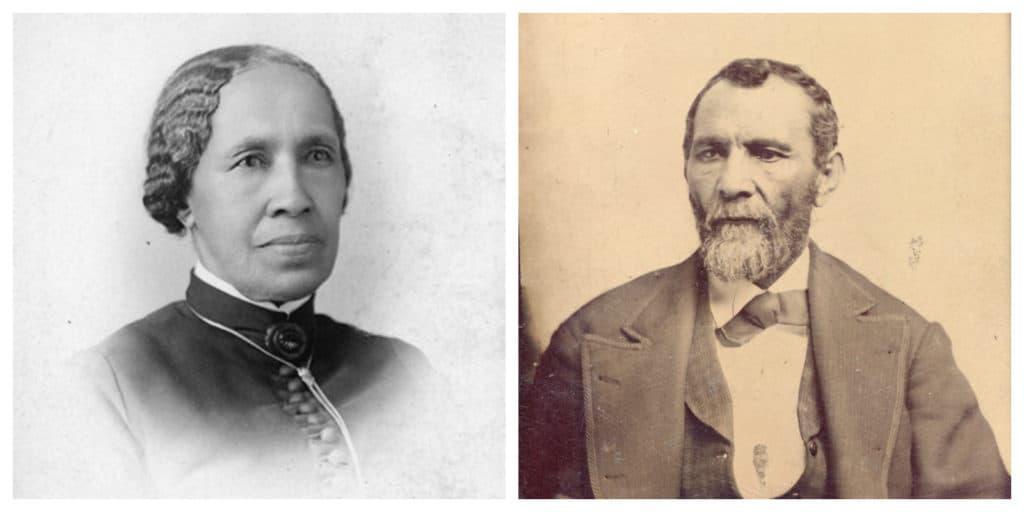

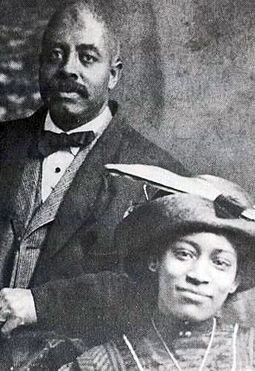

The first Black immigrants (of African Descent) arrived in British Columbia from California in 1858. They settled in Victoria and Salt Spring Island, but began migrating to Vancouver in the early 1900s, making their homes in Strathcona, the East End, a multicultural and working-class neighborhood that saw successive waves of immigration to Vancouver from Europe and Asia – becoming the residential neighbourhood for Chinese, Japanese, Italians, Ukrainians, Polish, Scandinavians and other European and Asian settlers. They were joined by Black homesteaders from Alberta, who originally came from Oklahoma, and by Black railroad porters worked at the Great Northern Railway nearby. At its height in the 1940s, the Black population in Strathcona may have numbered up to 800 people.

Urban Renewal and Community Activism

Over the years, the Strathcona residents endured efforts by the city to rezone Strathcona making it difficult to obtain mortgages or make home improvements, and by newspaper articles portraying Hogan’s Alley and Chinatown as a centre of squalor, immorality and crime. Beginning in 1967, the City of Vancouver began leveling the western half of Hogan’s Alley to construct an interurban freeway through Chinatown. The freeway was ultimately stopped with organized community advocacy, but construction of the first phase – the Georgia viaduct – was completed in 1971. In the process, the western end of Hogan’s Alley was expropriated and several blocks of houses were demolished.

Residents: Stories from Union Street and the East End (Strathcona)

In 2009, Vancouver Moving Theatre created a “East End Blues and All That Jazz” a musical tribute to the East End’s historic Black residential neighbourhood. This was a historic show and as performer Thelma Gibson is quoted, ” there really is no cohesive community and that black people are “everywhere”. This is but one of the places we tell the stories of Black history in Vancouver, and BC.

The Black Strathcona website, plaque and video project share excellent stories of the people and places, 10 sites in Strathcona of interest.

In 2014, a Canada Post stamp was issued to commemorate Hogan’s Alley and Africville. A Vancouver Sun article shares quotes, and offers a less romanticized view.

A 2023 article in the Vancouver Sun, shares two former residents’ stories, Cookie Simonetta (1930s) and Randy Clark (1960s) who grew up in the 200-block of Union Street. Randy lived at 230 Union St. in Hogan’s Alley from 1965 to 1968, after moving to B.C. from California as a child and by then, very few Black people were living in the area, nor was the name in use.

Clark is the grandson of Vie Moore, of Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, at 209 Union. The restaurant was one of the last “chicken joints” and closed in 1980 (the PTM plaque is located close to the site of the original restaurant).

Elwin Xie, whose family ran Union Laundry, shares his memories of the area, and its interconnected history with Chinatown and Vancouver as a whole. He grew up working and living at Union Laundry in the 1960s.

Elder Larry Grant is of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm and Chinese Canadian ancestry, lived in Chinatown and attended Strathcona Elementary during part of his childhood.

Scout Magazine’s You Should Know About Sarah Cassell and Sarah’s Cafe by Christine Hagemoen Vancouver history has always been full of entrepreneurial women, and Sarah Cassell of Montserrat was no exception. She ran Sarah’s Cafe from 1951 to 1984 on 218 E Georgia Street. Read it to learn more about one of the many chicken joints and cafes run by Black women in Vancouver.

Legacies and Futures

In recent years, there have been significant efforts to commemorate the neighbourhood, through community and government initiatives such as the stamp issued by Canada Post in February 2014 as part of Black History Month. Artists such as Andrea Fatona and Cornelia Wyngaarden, Wayde Compton, and Stan Douglas’ circa 1948 , have explored Hogan’s Alley in their work.

The Hogan’s Alley Society has partnered with the Portland Hotel Society (“PHS”), the city of Vancouver and BC Housing to deliver a 52-unit temporary modular housing development on the Hogan’s Alley Block, named Nora Hendrix Place, and is working on a MVRD Black Experience Project to begin mapping out the diverse experiences of people of African descent (Black) in Metro Vancouver.

On Vernon Drive, Rise Up Marketplace has been in operation since 2022 occupying a historic corner store featuring local and global goods with African connections. And on Keefer Street, Juke’s Fried Chicken has been operating since 2016.

A 2022 Montecristo article by Kevin Chong, shares aspects of the history and also new and current additions to the community like the Vancouver Black Library space.

Cross Cultural Walking Tours exists to tell the many layers of cultural stories of the Strathcona neighbourhood.

The City of Vancouver has an MOU for future plans on a Black Cultural Centre, with the impending Georgia viaduct removal which have been delayed since the plaque was presented in 2013.

Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project and VHF worked towards the Places That Matter plaque you see on the side of Union and Main Street. A short walk down Union Street eastward will bring you to the former Fountain Chapel. It was an active black church, part of the A.M.E (African Methodist Episcopal) from 1918-1950s.

Beyond Hogan’s Alley & Strathcona: Did you Know? Black residents can be found since the beginning of the City’s existence, in neighbourhoods from the West End, Mount Pleasant, South Vancouver, Kitsilano and Grandview and more. Archival research needs to be done on these diverse stories, and we will be working to feature these connections in the future. Please submit a story if you have a connection to share.

Video Resources and Projects

Related Organizations and Online Resources

Nearby Places That Matter